Missed Signals: The Impact of Race and Ethnicity on Diagnosis and Treatment in Dermatological Disease

For patients with eczema or psoriasis, race-based disparities can affect the trajectory of disease

Racial biases happen in many areas of healthcare, from research to therapeutic development to patient interactions with providers. Dermatological conditions have a unique risk of bias, as guidelines and clinical assessments are often based on presentations on lighter skin and are informed by clinical research on predominantly light-skinned people. Misdiagnoses are more common in people with darker skin, and disease severity can be dramatically underestimated, leading to delayed diagnoses, inappropriate or delayed treatments, higher rates of severe disease, and, ultimately, worse long-term outcomes.

Two dermatological conditions with notable race-based disparities are atopic dermatitis (AD), also known as eczema, and psoriasis. In the U.S., AD is more common, more severe, and more persistent among Black children than White or Hispanic children, putting them at increased risk of subsequent type 2 inflammatory conditions such as asthma. Psoriasis, on the other hand, is on record as being more common among White patients, but rates in non-White groups may be underestimated due to challenges in diagnosing patients of color, according to the National Psoriasis Foundation. Research has found that Black and Asian psoriasis sufferers are more likely to have larger portions of the body affected. It has also been found that, compared to the White population, Black, Asian, and other non-Hispanic minorities are roughly 40% less likely to visit a dermatologist for treatment.

In this analysis, we explored differences in incidence, progression, and use of gold-standard treatment for AD and psoriasis across racial and ethnic groups. Using 2021 data from our Healthcare Map™, we leveraged our Prism software to understand how different patient cohorts across symptoms, diagnoses, and treatments varied, particularly where a broad range of obstacles for access to optimal care could exist. Here’s what we found:

Among all patients with AD, children of color ages 3 to 12 made up 12% of newly diagnosed cases, compared to 7% of White children.

This aligns with research showing that children of color in the U.S. are more likely than White children to have not only AD, but severe and persistent AD. Children who develop AD are at higher risk of developing subsequent type 2 inflammatory diseases such as asthma. Prior research has shown that Black children with AD are also more likely to have asthma but are less likely to be evaluated by an allergist compared to White children.

Black patients are more likely than White patients to have uncontrolled AD.

Uncontrolled AD is defined as therapeutic failure after topical therapy and phototherapy. For this analysis, we defined uncontrolled disease in patients as three consecutive years on a topical therapeutic and no history of using Dupixent, the gold-standard systemic therapeutic for moderate-to-severe AD. Uncontrolled disease was seen in 32% of Black AD patients despite representing 23% of all AD diagnoses that year. In comparison, 38% of White patients had uncontrolled disease but represented 43% of AD diagnoses.

Patients of color were less likely than White patients to receive the gold standard of AD treatment.

Among all patients newly diagnosed with AD in 2021 who received Dupixent for the first time within one year of diagnosis, 58% were White despite making up 46% of all new diagnoses. Black and Hispanic or Latino patients received Dupixent within a year of new diagnosis at a lower rate: 16% and 10%, respectively. Black patients made up 20% of newly diagnosed AD cases and Hispanic patients 19% in 2021.

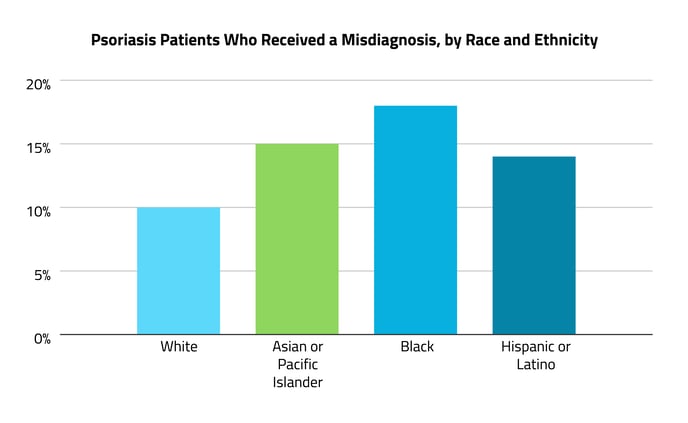

Psoriasis patients of color were more likely than White patients to have received a misdiagnosis.

About 10% of White patients received a misdiagnosis before their psoriasis diagnosis, but this was more common among patients of color: 18% for Black patients, 14% for Hispanic patients, and 15% for Asian patients. The most common misdiagnosis among all patients was AD or a “nonspecific rash.”

Among those diagnosed with psoriasis, patients of color received biologic treatment just as often as White patients.

Unlike in AD, patients who had been newly diagnosed with psoriasis received biologic treatment at a similar rate across our racial and ethnic categories. Treatment of psoriasis is similar to AD, where it’s generally recommended that moderate to severe disease be treated with systemic approaches, including light therapy or biologic agents; cost can be a major consideration with biologic medications, however.

Disparities were seen in the use of systemic treatment for AD, but not for psoriasis, which may reflect more equity in care; however, it is possible that other factors are contributing to this difference. For example, psoriasis patients may be diagnosed at later stages of progression due to the higher rate of misdiagnosis.

Elucidating racial and ethnic disparities in the diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes of skin diseases is an important step in moving toward health equity. Specialists working in dermatological diseases have a unique challenge in light of existing research, guidelines, and provider practices that may put patients with darker skin at a disadvantage. On top of the higher risk of misdiagnosis, potential language barriers may also be especially consequential for patients of color. First-line treatment for mild to moderate disease can include approaches that require nuanced communication, such as careful skin-care practices and lifestyle changes to limit exacerbating factors.

Komodo Health’s software suite, built atop the real-world data of more than 330 million patient lives, is uniquely positioned to quantify, define, and pinpoint the moments in healthcare journeys where racial and ethnic disparities emerge. While the causes of these disparities are complex and multifactorial, this tool can support updates to provider education and highlight the need for inclusive clinical research.

Read more of our work in elucidating racial and ethnic disparities in  and

and  .

.

To see more articles like this, follow Komodo Health on Twitter, LinkedIn, or YouTube, and visit Insights on our website.