Waiting for Coverage at a Cost: Payer-Based Differences in Huntington's Disease and ALS

For Americans newly diagnosed with serious disease, navigating the ins and outs of healthcare insurance can complicate an already difficult time. The weight of this burden varies widely among individuals and communities and across diseases and manifestations of illness. The costs of delays can be high: they can significantly increase individual and collective burdens of disease, and medical bills remain the top cause of bankruptcy in American families.

Wait times for Medicare coverage can be especially devastating for patients with fast-moving and disabling diseases. Progressive, terminal, and rare neurodegenerative diseases require increasingly intensive care and management over time, preventing patients from working at later stages of disease. Most have to wait until age 65 to become eligible for Medicare but can be approved earlier if they qualify for Social Security Disability Insurance. However, they must complete two waiting periods totaling nearly two and half years — a delay they often can’t afford, financially or in terms of their disease progressing. It’s estimated that 1.6 million people with disabilities are currently in this waiting period for Medicare coverage.

Patient advocacy organizations have worked hard to have exceptions to these wait periods made. In amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a neurodegenerative disease typically diagnosed in adults ages 55 to 75, advocates succeeded in having a two-year wait period dropped in 2001. The additional five-month wait period was dropped in 2020. Advocates are currently working to be granted the same exemption for comparable diseases like Huntington’s disease (HD), in which symptoms typically begin between ages 30 and 50. The HD Parity Act was introduced to the House of Representatives in 2021, and efforts to pass the legislation are ongoing.

May is Huntington’s Disease Awareness Month, and we wanted to learn more about the disease severity, progression, and access to home healthcare in patients with HD and ALS on commercial insurance and Medicare. For this analysis, diagnoses for HD and ALS were defined using ICD9-CM and ICD10-CM codes. Patients diagnosed in 2019 were included if they had no markers of severe/late-stage disease prior to diagnosis. They were then grouped by insurance type and tracked for the new occurrence of markers of severe/late-stage disease. These included dependence on other enabling machines and devices, gastrostomy interventions such as a feeding tube or related supports, and acute respiratory failure (with or without hypoxia).

Here’s what we found:

For both ALS and HD, newly diagnosed Medicare patients were more likely to develop markers of severe disease in one to three years after diagnosis, compared with their commercially insured counterparts.

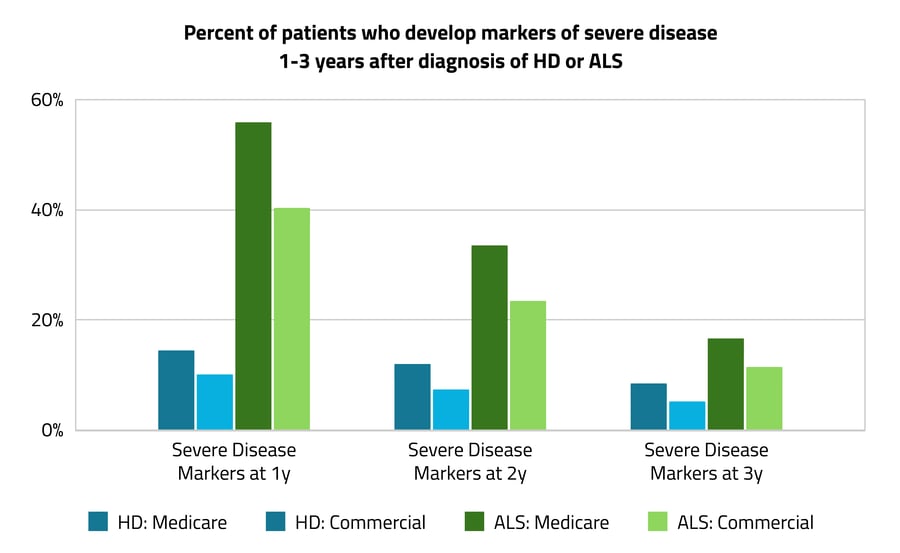

Among newly diagnosed patients without a history of severe disease, 16% more ALS patients on Medicare developed at least one severe disease marker a year after being diagnosed compared with commercially insured ALS patients (56% vs. 40%). Among HD patients, 4% more patients on Medicare developed at least one severe disease marker in the same time frame compared with commercially insured HD patients (14% vs. 10%). This difference persisted when looking for severe disease markers two and three years after diagnosis. In the years just after diagnosis, ALS patients experienced significantly more markers of severe disease than HD patients overall.

In the years just after diagnosis, ALS patients experienced significantly more markers of severe disease than HD patients overall.

As shown above, 56% and 40% of the ALS patient groups developed markers of severe disease one year after diagnosis compared with 14% and 10% in the HD groups. ALS patients on Medicare were 42% more likely to develop markers of severe disease after a year compared with HD patients on Medicare. ALS patients on commercial insurance were 30% more likely than HD patients to develop severe markers after a year. This is expected given that ALS typically progresses faster than HD.

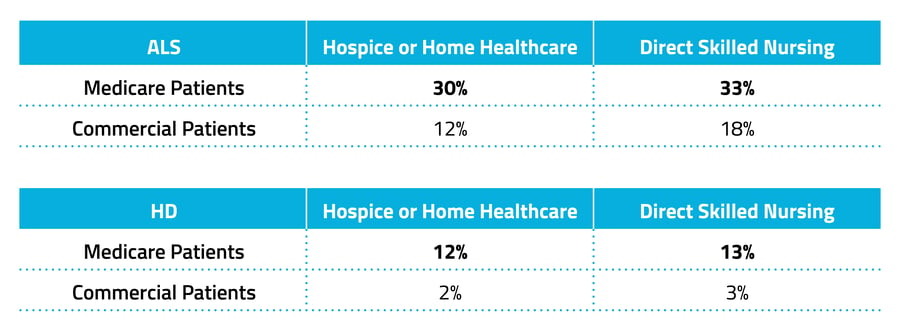

For both ALS and HD, patients on Medicare were 17% more likely than those with commercial insurance to receive in-home healthcare.

In a second analysis, we looked at patients over a longer time period, from 2021 to 2022. Komodo’s Prism's patient journey feature was used to track encounters for the two years after diagnosis. Among HD and ALS patients, 26% of Medicare patients had claims for in-home healthcare, compared with just 9% of commercially insured patients — a 17% difference. Medicare patients were also 15% more likely to receive direct skilled nursing services in their homes or in hospice settings — 28% of Medicare patients compared with just 13% of commercially insured patients. As this finding was among patients with markers of severe disease, who would likely benefit from in-home/in-hospice specialty care, this may indicate that more commercially insured patients are paying for these services out of pocket and/or are less likely to receive them overall. Excluding the use of private services, differences in utilization across insurance types may reflect coverage limitations, co-pays, or other unmanageable out-of-pocket fees for commercially insured patients. Among both ALS and HD patients with markers of severe disease, commercially insured patients were an average of nine years younger than those on Medicare.

Among both ALS and HD patients with markers of severe disease, commercially insured patients were an average of nine years younger than those on Medicare.

The average age of ALS patients with severe disease on Medicare was 67. Among those with severe disease on commercial insurance, the average age was 58. HD patients with severe disease on Medicare were 62 on average, compared with age 53 on average for those on commercial insurance. That the average age of HD patients is three years below the typical age of Medicare eligibility points to the high number of patients that have gone through the waiting period for disability-based Medicare eligibility. The age gap between payer types suggests that patients not covered by commercial insurance may be waiting longer to initiate care. Additionally, while severe symptoms tend to manifest more slowly in HD than in ALS, they manifest earlier in life, supporting the need for earlier access to coverage.

This analysis highlights payer-based gaps in outcomes and care across ALS and HD Medicare and commercially insured patients. Higher rates of severe disease were seen, as expected, in patients with Medicare. While several factors could be contributing to higher utilization of in-home and hospice claims from Medicare patients, commercial coverage may present its own barriers compared with Medicaid/Medicare coverage for patients without ample financial resources to cover co-pays or private care out of pocket.

Komodo Health has an industry-leading capacity to generate payer-based insights from longitudinal patient journeys. Here, we see that wait times and insurance-based barriers to care are especially important for patients with fast-moving, disabling diseases like HD and ALS. While policies do their best to address healthcare issues broadly, when it comes to health and disease, one size often does not fit all. As a part of our mission to reduce the burden of disease, we hope our insights can support the development of disease-specific policies so that more Americans can have timely access to the most appropriate care.

Check out more of Komodo’s disease-specific insights in our research brief on racial disparities in in-patient and emergency care across three chronic diseases.

To see more articles like this, follow Komodo Health on Twitter, LinkedIn, or YouTube, and visit Insights on our website.