Panic Attack or Heart Attack? Women With Myocardial Infarctions Are More Likely To Be Misdiagnosed and Undertreated

Male-centered clinical guidelines and a lack of provider awareness may be contributing to treatment delays among women experiencing heart attacks.

Throughout history, women’s physiological symptoms have been commonly and persistently minimized and misdiagnosed. “Hysteria”, a nebulous diagnosis applied to female patients as early as 4000 B.C, was included in the DSM until 1980. Over the years, this diagnosis has attributed symptoms of all kinds to “female problems” ranging from unfulfilled sexual desire to possession to a resistance to housework. The ancient Greeks once believed symptoms were caused by the uterus itself wandering around the body. As late as the 1990s, research still suggested that between 30% and 50% of depression diagnoses in women were misdiagnoses.

Cardiovascular disease is one therapeutic area that is rife with this gendered history. While sudden heart attacks are more common in men, women experience worse myocardial infarction (MI) outcomes. Younger women, specifically, experience worse outcomes than both men of the same age and older women. The reasons are multifold. While heart attack symptoms can often present similarly despite gender, women are less likely to present with “classic” chest pain and are more likely to present with atypical symptoms such as weakness, fatigue, and indigestion. They may also describe their symptoms differently than men and, like their providers, may be more likely than men to attribute their own symptoms to stress or anxiety. Researchers in Canada found that stereotypically or historically feminine-associated traits such as soft-spokenness were among the clinical predictors of delays in diagnosis and treatment for women experiencing heart attacks. Women experiencing an MI are less likely to receive guideline-adherent treatments and tend to have more delays in critical treatment than men.

Guidelines and provider education are also shaped around male presentations of MI, as women are generally underrepresented in cardiovascular research. They are less likely to receive CPR in the field and have a higher rate of in-hospital mortality after heart attacks; traditional diagnostic tests such as electrocardiograms may be less likely to provide definitive results. After diagnosis, women may be less likely to be referred for appropriate therapeutic treatment.

Women do have certain predispositions for MI risk. They tend to be about a decade older when they have an MI, have unique hormonal-related risks due to menopause, pregnancy, and comorbidities such as polycystic ovarian syndrome, diabetes, and autoimmune diseases, which are more common in women, and can increase the risk of heart disease. Women may also have a higher risk of certain complications following a heart attack and tend to respond differently to interventional therapies than men.

To get an up-to-date snapshot of gender differences in the presentation and treatment of MI, our analysts looked at the symptoms and immediate clinical responses in nearly 900,000 MI patients in 2022. Here’s what they found:

Women were twice as likely as men to present with nausea ahead of an MI.

Women were also 32% more likely than men to present with malaise and fatigue and 12% less likely to present with classic symptoms, such as left-sided chest pain and angina. Women who present exclusively with atypical symptoms — who lack classic symptoms, or who describe those symptoms differently than what’s typical — are at particular risk of misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis.

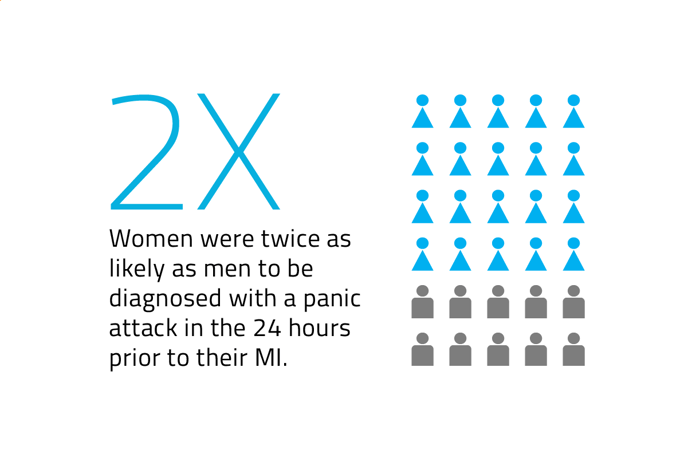

Women were twice as likely as men to be diagnosed with a panic attack in the 24 hours prior to their MI.

As anxiety symptoms were likely related to their MI, this suggests significant delays in diagnosis and missed opportunities for crucial early treatment. It also presents a pivotal window for meaningful updates to guidelines for diagnosing women who present with anxiety and have other risk factors for cardiac emergencies.

Women were 60% less likely to receive thrombolytic therapy than men (aspirin, clopidogrel, and/or heparin) in the 48 hours after an MI diagnosis.

Women were also 70% less likely to receive percutaneous intervention (stent, dilation, angioplasty) in the 48 hours after their diagnosis than men. This is in line with research showing that women with MIs are treated less aggressively with fewer cardiac procedures and have higher in-hospital mortality.

This data highlights the importance of inclusivity in clinical research and education of the public and providers alike about gender-based differences in MI presentation. A lack of provider and patient knowledge will continue to lead to unnecessary misdiagnoses, delays in care, and shorter therapeutic windows. Efficient and unbiased interventions will save lives, minimize long-term complications, and lessen unnecessary systemic burdens through shorter hospital stays and healthier patients in the long term. Komodo Health’s Healthcare Map™ and software tools are uniquely positioned to provide the evidence stakeholders need to pinpoint and enact the highest-impact healthcare solutions. In our mission to reduce the burden of disease, we will continue to provide accurate and up-to-date insights on real-world patient experiences to help close the gaps in health disparities of all kinds.

Read more of our work elucidating racial and ethnic disparities in  and

and  .

.

To see more articles like this, follow Komodo Health on Twitter, LinkedIn, or YouTube, and visit Insights on our website.